Before last Thursday, I hadn’t bathed in an entire month. I’ve showered, to be specific. But bathing became a luxury, one in which I found myself pining for during my walk home this evening when it began to rain. I prayed it would rain so hard I would get soaked down to the balls of my feet. But the drops stayed as such, and I entered our apartment nearly dry to the bone. Baths have been the one way I have figuratively and literally soaked off any love or loss. In a depression in the spring of 2021, my friend Autumn mentioned she had passed the daytime hours with a long bath, and I took to this and began to do it too. Take the kids to school. Listen to Arooj Aftab, pray, and try not to get back in bed. Bathe. Soak. It was EMDR and Parts Therapy, friends, and some time, but eventually, my need for the routine tapered off. The dark side of my brain began to capitulate, as if it was some small person back-stepping into a familiar room. I mention this only to note the importance of them and how the lack of it lately does not signify some great “unlearn.” In fact, if you look at wellness as a toolbox, the regularity of my baths since that spell has been a way to stave it off. So when I took one on a trip last week for a story, I made a note. And in coming home today made another. I want to hear my body, which is asking to steep in tepid waters in this apartment on the hill. So I will. That same week of the trip and the bath, I fell upon an essay on

from an author who shared excerpts from her book published in 2021. The words read like a person who knows what the f they’re doing and I wish I saved it or knew her name. Tonight, I bathe. But as I look back at the work I was doing during that time of daily baths (healing and writing something that has been in the world for nearly six months exactly) I’d like to borrow that author’s strategy and share excerpts from it with you. Not only in hopes that it reaches you wherever you may be, but also so that I may remember to visit and stay close to the things that work.P.S If you are in the Washington, DC area, I will be in conversation with Glory Edim at Mahogany Books on May 14th, at 7 pm. You can RSVP right here.

I’ll be at Catbird in Georgetown doing a workshop on May 15th. You can RSVP right here.

Now to the excerpt…

I moved in three weeks after stepping foot in it, and I no longer starved in fear that stress would make me heave whatever was in my stomach back at my feet. I didn’t snap at the sound of my landlord knocking at my door. Instead, I covered the living room in plants, the long white table in flora, and was dragged past my stoop by friends to jump a game of double Dutch at the playground to heal. I made love with someone new under the vaulted ceilings of a temple as the winter sun shined on my brown stretch-marked body, and I felt the gratitude in the sinner and the sanctified. I was holy ground; unfolded and vulnerable stratum.

We can’t choose the bodies we inhabit, but for many of us, home is an intrinsically personal decision dreamed about for a lifetime and known within seconds of entering a place. Like sex, you know when two parts just fit. Architectural historian Beatriz Colomina opens her well-known argument in Sexuality and Space with this: “The politics of space are always sexual, even if space is central to the mechanisms of the erasure of sexuality.” In that same body of work, Colomina looks at a house designed for Josephine Baker by Adolf Loos, one of the most influential European architects and theorists of the late nineteenth century. Loos repeated what he did in his other work, creating open spaces that looked like mirrors representing the Freudian psyche. The exterior wears a masculine mask; the spaces are ambiguous and split. “The eye is directed towards the interior, which turns its back on the outside world; but the subject and the object of the gaze have been reversed,” writes Colomina. In the Baker house, which rids itself of domestic life entirely, there is a swimming pool that can be entered from the second floor. The pool, an often privatized activity, becomes the center as a salon. Colomina adds, “The most intimate space—the swimming pool, paradigm of sensual space—occupies the center of the house, and is also the focus of the visitor’s gaze.” She goes on, “ But between this gaze and its object—the body—is a screen of glass and water, which renders the body inaccessible.”

I had been obsessed with this architectural theory from Colomina since first reading it. I was stuck on her lines and, in truth, unable to read further because the first itch had been satisfied enough. But later, I read on and became even more of a devotee to the concept—and the social constructs and contradictions that spring from it. When explaining the misfortune of the Josephine Baker house, particularly Loos’s philosophy behind it, Colomina summarizes:

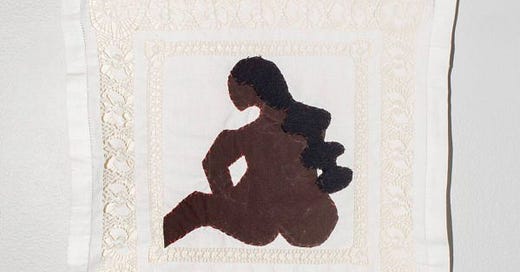

The image of Josephine Baker offers pleasure but also represents the

threat of castration posed by the “other”: the image of woman in

water—liquid, elusive, unable to be controlled, pinned down. One

way of dealing with this threat is fetishization.

The Josephine Baker house represents a shift in the sexual status of

the body. This shift involves determinations of race and class more

than gender. The theater box of the domestic interiors places the

occupant against the light. She appears as a silhouette, mysterious

and desirable, but the backlighting also draws attention to her as a

physical volume, a bodily presence within the house with its own

interior. She controls the interior, yet she is trapped within it. In the

Baker house, the body is produced as spectacle, the object of an

erotic gaze, an erotic system of looks.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to With Love, L to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.